At the recommendation of my friend Spencer, I recently began reading the Italian novelist Ignazio Silone’s The Abruzzio Trilogy, beginning with his 1933 novel Fontamara. It is an extraordinary bit of social-realist inflected anti-fascist satire, and I found myself quickly devouring it and eager to begin the next book in the series. It’s a very short book, and if by the end you don’t find yourself deeply moved and inspired by the tragic character of Berardo Viola, I don’t know what to tell you.

I won’t quote anything from the book here (you should read it yourself), but will provide a few pieces from the paratext that I found of particular interest. Both are taken from the author’s “Note on the revision of Fontamara“ [written from Rome in 1960]

I must say something about the relations between me and my books. I identify myself completely with Hugo van Hofmannsthal’s claim that writers are a human category for whom writing is more difficulty than it is for anyone else. The reason for this becomes plain to me whenever I am on the point of finishing a book. Finishing it seems to me to be an arbitrary and painful act, an act against nature, at any rate my nature. I live in a close communion with the characters in my stories that cannot be broken from one day to the next; I go on thinking about them and letting my imagination play with them, and thus the book goes on living and growing inside me and changing even after it has appeared in the bookshop windows. …

If it were in my power to change the mercantile laws of literary society, I might well spend my life perpetually writing and rewriting the same story in the hope of at last understanding it and making it understood, just as in the Middle Ages there were monks who spent their whole lives painting and repainting the Savior’s face, always the same face, yet always different.

George Oppen wrote, in section 27 of his remarkable long poem “Of Being Numerous”: “one must not come to feel that he has a thousand threads in his hands, / He must somehow see the one thing; / This is the level of art / There are other levels / But there is no other level of art”.

I hear in Silone’s wish, something of a kindred feeling, just as I find in the handwritten title of the cafoni’s newspaper and the repeated query which echoes out from the novel’s closing chapter: “What are we to do? What are we to do?” a stricter, more searching (and more socially engaged) version of the question posed by the contemporary American poet Mary Oliver in these concluding lines from her poem “The Summer Day”: “I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down / into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass, / how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields, / which is what I have been doing all day. / Tell me, what else should I have done? / Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon? / Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?”

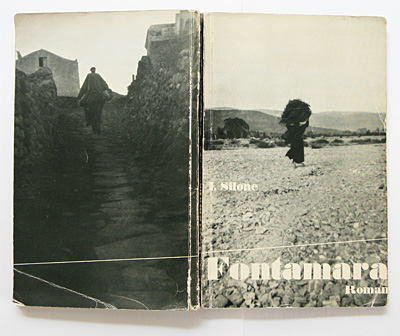

Featured image: The cover of the 1st edition of Ignazio Silone’s Fontamara