I know I keep writing about Oppen and his letters, but I just can’t help it. Today I was typing up my notes from his mid-60s letters, and remembered a pretty tremendous letter he wrote to Lita Hornick, then the managing editor of Kulchur, in response to Kulchur‘s decision to print “Soirées,” a Felix Pollak poem he wrote lampooning Denise Levertov’s “Matins.” Levertov was, at the time, the poetry editor of The Nation.

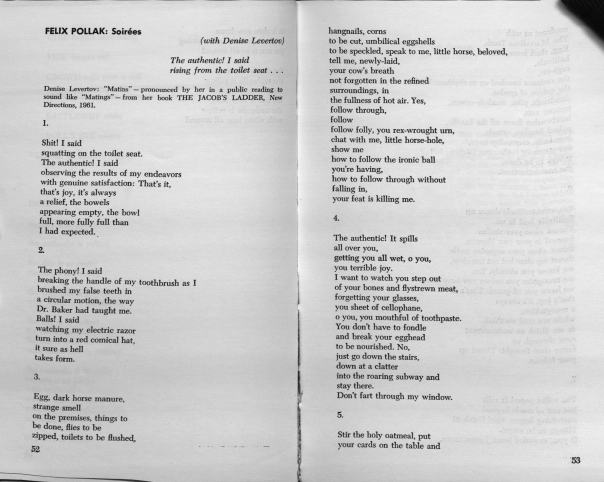

I was particularly interested in this little literary spat because I’ve been a curator for the FELIX reading series I hadn’t read Pollak’s poem, and I wanted to see what the fuss was all about, so I went to Special Collections in the UW-Madison library, dug up the issue of Kulchur (Vol. 18, summer 1965) it appeared in.

I’ve scanned and included Pollak’s poem below:

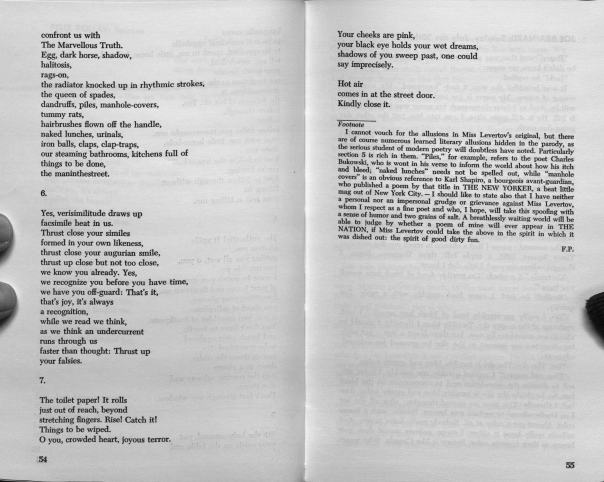

Pollak claims in his footnote that he has “neither a person nor an impersonal grudge or grievance against Miss Levertov,” and then attempts to place the onus of responsibility onto Levertov–almost as if he believed he could bully her into publishing his work, writing that “a breathlessly waiting world will be able to judge … if Miss Levertov could take the above in the spirit in which it was dished out: the spirit of good dirty fun” by whether or not Levertov chose to publish in some future issue of The Nation. Others may read this differently, but my impression of Pollak’s behavior in this interaction is that of a rather cruel and dull bully, one who I suspect may have felt particularly spurned by having his poetry rejected for publication in The Nation by Levertov, though I understand that his personality had far more nuance and range in other settings. In any case, here’s Oppen’s letter to Hornick, the woman who decided to publish Pollak’s poem:

Dear Lita:

I’d like to suggest to you that if Kulchur prints such things as Felix Pollack’s attack on Denise Levertov, the magazine will become an instrument for the blackmail of editors. I would like most seriously to suggest to you that it is within the province of an editor to prevent that use of a magazine. Moreover I think that kind of attack on a woman poet — deliberately speaking of shit, menstruation, wet dreams, falsies — is obviously injurious to poetry, to the freedom of poetry, an attempt to destroy a poet, tho of course it will not do so.

I recognize that this is very much in the tone of a letter to a local newspaper; I mean it in approximately that spirit. I think the piece is unforgivable, not so much to have written — it is common to be very angry at editors who refuse a poem — as to have printed. I think really, really, really, whatever one’s debt to the poor, the unknown, the furious, I think one need not print such things. And I write to tell you so.

With regards, tho, of course,

Rachel Blau Du Plessis, the editor of Oppen’s selected letters, writes in her notes on this letter that when she read this letter to George and Mary in May of 1982, George’s response was: “Let’s send it again.” Assuming that dementia had destroyed much of Oppen’s faculties at this time, in this case the impulse seems both wonderfully sharp and possessed of a crucial lucidity.

I can’t remember exactly when I became aware of the practice, but at some point in my life I learned that my for any purchase over $100, my parents had a rule that they always needed to sleep on the decision for at least a day–that way they’d avoid rash impulse buys and be more careful and prudent in their spending. I’m very much my parents’ child in this regard, and try to practice the same thing in regard to my own spending habits. I wonder whether a similar rule might not be helpful in regard to the words we publish, commit to print, or otherwise make public? Oppen’s remark that “whatever one’s debt to the poor, the unknown, the furious, I think one need not print such things” seems so accurate and so precise to me for many of the same reasons that I often feel embarrassed to read my teenage journals–the ephemerality of sentiment combined with the failure of impulse control in these situations does not produce the kind of expression that I feel worth dignifying or preserving through poetry.

In some respects, the ubiquity of social media and personally-branded expressive digital publishing platforms seems to have moved petulance and public expressions of idiocy, cruelty, or snap judgments into a particularly important role in contemporary culture. Witness the rise of sites like Undetweetable and Politwhoops and the way that the web economy’s drive for page views had Gawkerized news content and journalistic standards. I suppose what I’m saying is not that there is no place for “first thought, best thought” philosophies, or for content produced to drive up page counts. Certainly, there are many editors who would defend Hornick’s decision to publish Pollak’s decision as shrewd business–it lampooned a semi-famous figure, it titillated and perhaps delighted some of its readers, it prominently featured sex and excretion, and it perhaps even generated a bit of buzz, some conversation. Fair points, I suppose. It’s just that for me, poetry does (and should do, ought to do, even must do) something else. Poetry editors can (and do) publish whatever they like for whatever reasons (no matter how whimsical, haphazard, or even capricious they may be) the want, all fine and true. That doesn’t mean that we must respect them or their editorial judgments. As for me, I’m going to start drafting letters to editors–both appreciative and otherwise–but I won’t send them until I’ve slept on them for at least one night.

One response to “How to Write a Letter to the Editor”

I totally agree with you. Any time I write a blog post/letter against something I always wait a day to put it out there. It may still sound angry (hopefully justifiably) but i’ll know that I really believe what I’m saying. And I respect editors a great deal for their jobs–especially since they have to put up with nuts.